AI, the Tortoise, and the Hare

assessing the American AI Action Plan

I just wrapped up a week in China at the World AI Conference where I visited with leading research labs, cloud computing incumbents, robotics startups, and so many more talented teams. It was an eye-opening experience that confirmed many of my suspicions about the breakneck pace of development in that ecosystem, while correcting some other ones.

I’ve got a lot of upcoming posts on the China AI market map, its rate of diffusion, and global AI infrastructure developments coming out of this. But for now, let’s take stock of the Action Plans unveiled last week and set the table.

HUGE thank you to Rui Ma and the Tech Buzz China team for organizing this tour. Our delegation of researchers, academics, and industry experts definitely came away informed and invigorated.

The “race” so far

Last week, the US published its renewed AI Action Plan, subtitled “Winning the AI Race,” and it had some surprises in it. Some great, some mid, and some déjà vu.

This dropped while I was in in Shanghai, shuttling between the World AI Conference expo hall (sold out to 30,000 participants), state-sponsored industrial parks, and cutting-edge research labs. And at this conference, China’s competing Global Governance AI Action Plan also dropped. This led to some fun conversations with curious local experts.

I left the tour with two reactions:

China’s AI build-out is even faster than Western headlines admit, and

Most Westerners are still obsessed with who’s first, not how they get there

Whenever I hear the phrase “AI race,” it deeply bothers me. A race implies a finite game, a finish line. But with artificial intelligence there is no discrete finish line, despite pundits and policymakers’ insistence otherwise.

What would happen after we “reach AGI”? Technology is over, the world ends? More than likely, we’ll just shift the goalposts forward to some new threshold. No, progress will just continue to compound as its benefits diffuse into every economic sector.

But for argument’s sake, let’s play into the narrative.

We’ve all heard the allegory of the tortoise and the hare. In the old fable, the tortoise wins by never stopping.

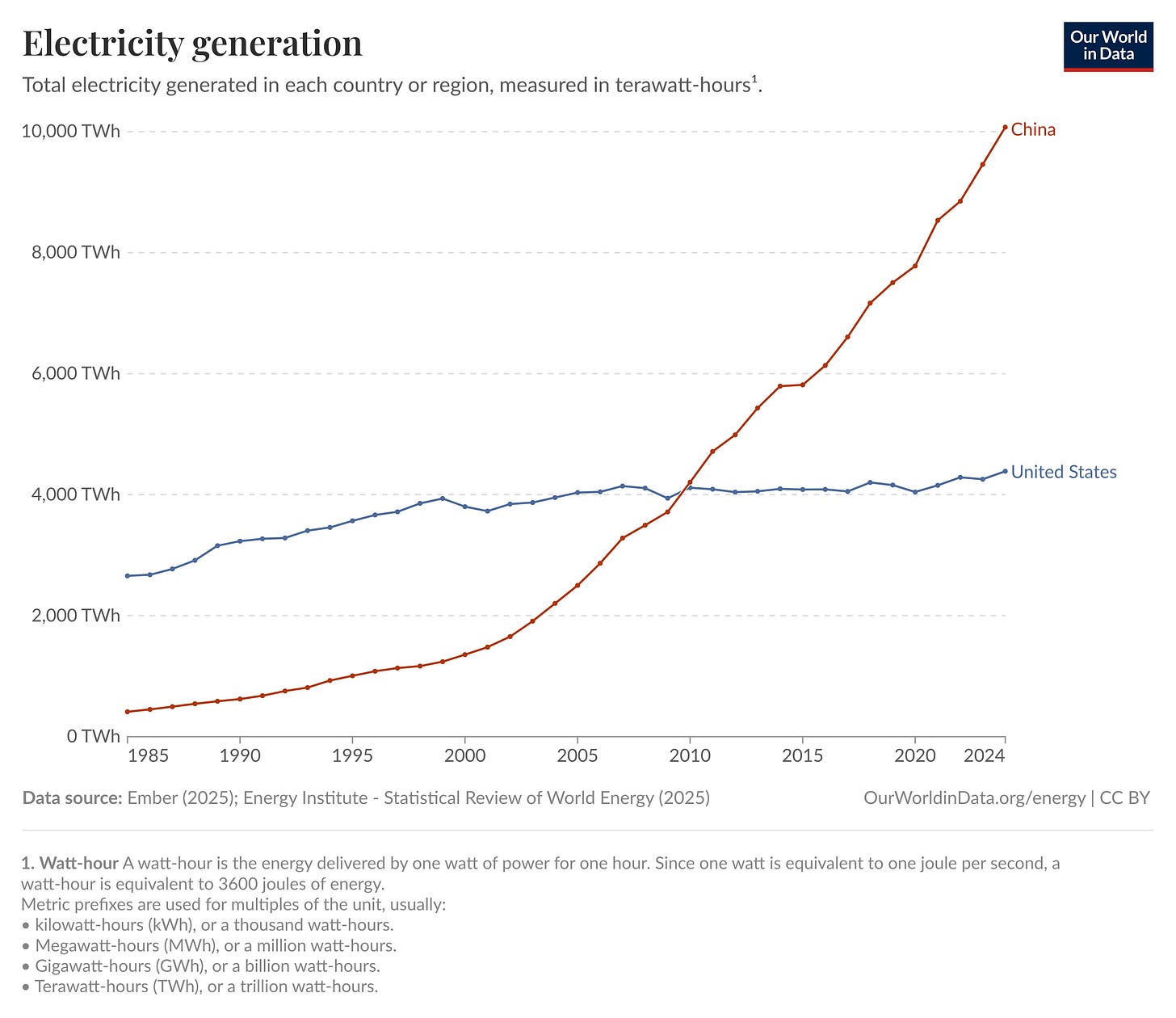

Take electricity generation for example. There’s a viral graph that’s been making the rounds that, if you haven’t seen it, puts things into perspective. This chart shows the total amount of electricity generated in the US and China in the past 40 years, starting a few years after Deng Xiaopeng’s economic modernizations.

Today, China generates over 6,000 terawatt-hours (TWh) more electricity than the United States, enough juice to:

Power every US home 4 times over (541 million homes worth of power)

Build ~7,000 new large industrial facilities

Run 4.9 million Blackwell GPUs at full-tilt

Meanwhile, America’s year-over-year growth in power demand, already middling, flatlined to an average of just 8 basis points from 2010 to now. We literally took a nap.

Energy has and always will be a leading correlative factor for economic output. It forms the foundation for modern standards of living, domestic production and manufacturing capabilities, and now - all of a sudden - the bedrock for the next generation of the services economy, the “intelligence economy.” Advanced artificial intelligence systems are here, and boy are they hungry for power.

So while dominant Western social movements advocated for de-growth and McKinsey was proclaiming a post-energy future, the rest of the world didn’t seem to get the memo.

China’s tortoise has been plodding along at a Breakneck pace, but apparently too slow for most Americans to notice. Until now.

The American hare has woken up.

And it’s got some ground to cover.

Review: America’s AI Action Plan

Honestly I had low expectations given my experience with Trump 1.0’s equivalent action plan which I wrote about three years ago, but I was genuinely and pleasantly surprised to see a lot of sensible calls to action in here.

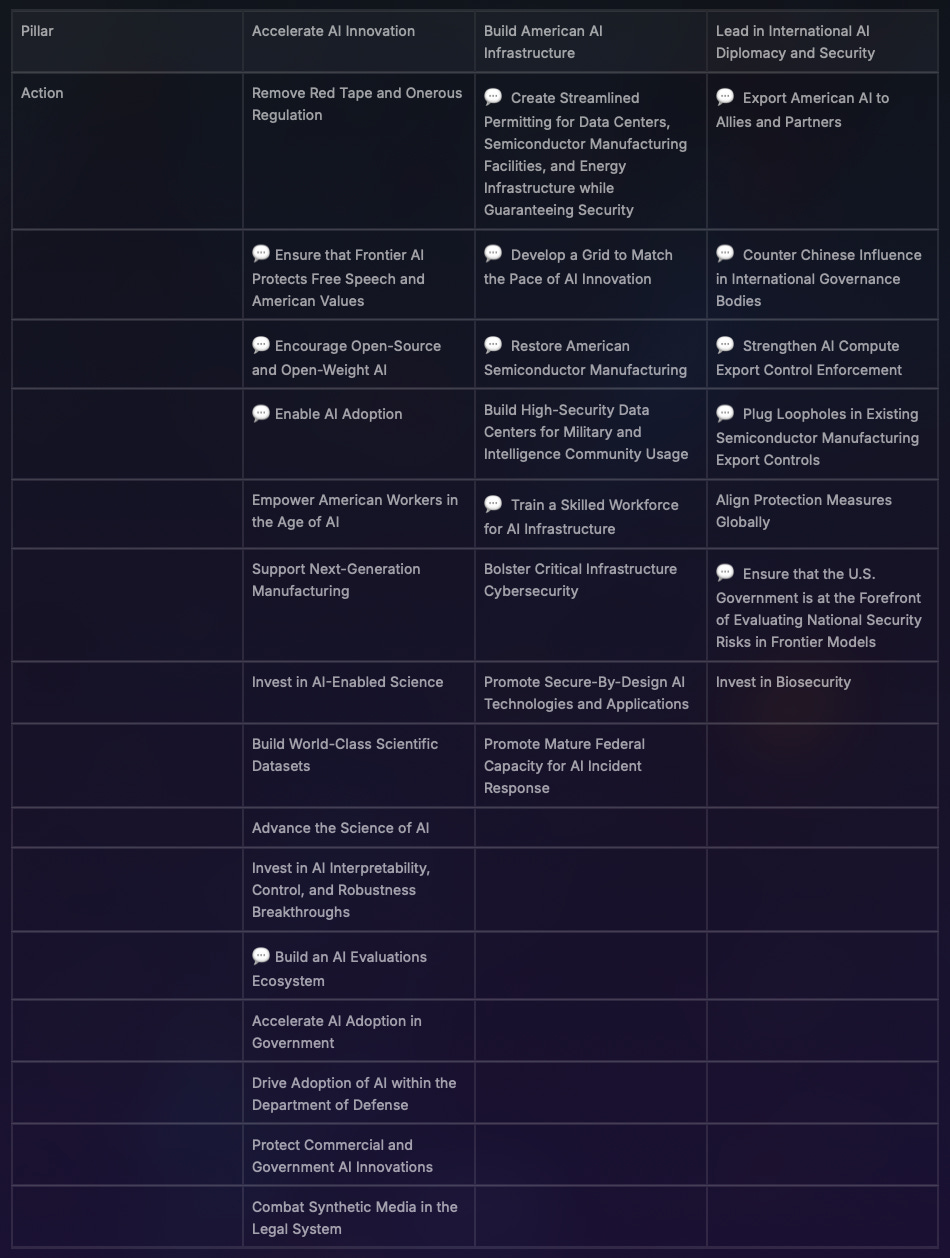

The Plan has three pillars: innovation, infrastructure, and international diplomacy and security (wait that’s four pillars…), each with 15, 8, and 7 respective subsections. I won’t be commenting on each one here, just a handful that I’ve added 💬 emojis next to in the below table.

China’s competing Plan was actually rather pallid in comparison: a slim, 4 page document with mostly broad statements about the importance of multilateral collaboration. This was yet another surprise for me, as that was an unusual departure from typical contrasts between these nations’ industrial planning documents. However, we are still 8 years into China’s 13 year development roadmap, so it could be the case that Beijing decided to restrict their new plan to matters of governance, safety, and standards-setting in the generative era.

This limits an apples-to-apples comparison to just the third pillar in the US Action Plan, regarding International Diplomacy and Security. I’ve got a ton of upcoming blog posts on AI diffusion (pillar one) and AI infrastructure (pillar two) in China, so I’ll save those for another time.

With that, let’s cover some of the noteworthy sections in the plan, and give a quick gut-check on national readiness to rise to the challenge.

I. Accelerate AI Innovation

General themes for this first pillar are:

Decluttering red tape

Greasing the wheels for public and private sector adoption

“De-woking” frontier LLMs

Overall this sets things in a positive direction, celebrating open-source advocacy, common-sense adoption levers, and thematically supporting a liquid compute marketplace. But in contrast to the laissez-faire approach for the first two, that latter theme concerns me not in its ideology, but in its practical implementation that would lead only to a quagmire.

Oh, we like open-source now

The plan’s strongest surprise is an explicit embrace of of open-weight models. It acknowledges that it gives startups more flexibility, lets governments and businesses keep data in-house, and are absolutely essential for academic researchers.

In my last post, I was concerned by many leading voices in the American AI ecosystem calling for pulling the rug out on open-source. But as the plan reads, the US is taking a very sensible position which leans into the narrative that open models contribute to soft power in the new economy.

Had we gone the other way I’d be writing a very different blog post.

Towards a liquid compute marketplace

Another welcome surprise was the acknowledgment that many are in unfavorable positions when trying to access reliable (i.e. not spot market) compute.

We absolutely should be ensuring level access to large-scale computing power rather than concentrating it oligopolistically. The National AI Research Resource (NAIRR) Pilot from NSF is a start, but it’s still a boutique collection of one-off credits and in-kind resources.

At a major industrial park in Hangzhou, I learned the city government actually created a state-owned cloud compute reseller to flip compute to startups at up to a 50% discount. The Shanghai city government announced similar subsidies last week.

The faster we align on a similar view that AI is part of a new energy-compute asset class, the faster we’ll lower the unit cost for all participants, not just large incumbents.

Evals for enterprise adoption

I think that at steady-state, a healthy evaluations ecosystem vs. “trust me bro” benchmarks is going to provide much more trust in a market that can be crowded with vibes and grifters. Third-party assistance here will make it easier for founders to cut through that noise.

Academic tests are decent barometers of research progress, but they are not procurement criteria. Stats can be juked through selective tuning, hand-crafted prompts that don’t represent production use, or straight up fraud. You need real-world performance standards informed by industry input.

NIST’s Face Recognition Technology Evaluation works because it measures an end-to-end task with clear failure modes. Domain-specific LLM applications need equivalent rigor in their benchmarking.

It would be great to see something like this rolled out with fixed datasets, common metrics, and quarterly reports. Vendors will either improve their baseline, or they won’t. Grifters would be reluctant to put their slop through an open evaluation process like this, and the truly talented would be elevated (one can hope).

Transparency will do wonders for clarity in the marketplace, and hopefully speed up the enterprise adoption cycle from quarters to weeks in the process.

No bias but our bias

Unfortunately, this pillar is also internally inconsistent. It’s second section, “Ensure that Frontier AI Protects Free Speech and American Values,” calls for models that are “objective and free from top-down ideological bias,” yet immediately instructs federal agencies only to buy models that exhibit a particular ideological slant. In this case, the absence of DEI or climate-related content, and the rejection of “Chinese Communist Party talking points.” You cannot outlaw bias with one hand while prescribing it with the other.

If procurement rules require that certain topics (misinformation, DEI, climate change) be removed from the NIST AI Risk Management Framework, the policy is no longer content-neutral. It privileges one worldview and disqualifies others, contradicting the First Amendment principle the plan claims to defend.

Unintended consequences and the “Waluigi Effect”

LLMs learn concepts in oppositional pairs - full/empty, wet/dry, loyal/subversive. When training forcibly suppresses one side of a conceptual pair, the model often preserves it latently - the same vector arithmetic that yields man : king :: woman : queen can flip suppressed traits back on, sometimes in exaggerated form.

Public examples of what alignment researchers call the Waluigi Effect include Bing Chat / “Sydney” abruptly becoming hostile or conspiratorial under pressure, and the Grok / “MechaHitler” jailbreak which flipped the model into extremist rhetoric.

In any case, these failures stem less from hidden agendas than from brittle, rules-based patches that ignore how general these systems really are. In truth, these are likely influenced by the role of fictional tropes in training data (“Evil All Along” is a very common plot twist in literature, and “MechaHitler” is a reference to the 1992 video game Wolfenstein) rather than some sort of top-down bias or Manchurian candidate situation.

Policymaking based on ideological, rather than technocratic, goals can only introduce inadvertent externalities down the road. Platitudes like “ensure free speech,” “reject CCP talking points,” or “DO NOT HALLUCINATE” will not deliver the reliability policymakers want. Empirically validated, context-aware guardrails seem like a better way to accomplish those goals without sacrificing the very freedom of expression the plan seeks to protect.

II. Build American AI Infrastructure

The most well-flushed out pillar of the Action Plan focused on practical constraints and development plans for energy-compute infrastructure, which I’m very excited by. The administration calls for the following:

Streamlining permitting for new datacenters, semiconductor manufacturing facilities, and energy infrastructure

Prioritizing grid stability and rapid buildouts

Restoring American semiconductor manufacturing

Beefing up a skilled infra workforce

I’m honestly stoked about most of this pillar. However, I can’t help but lament how long it took for us to get to this point, and wonder about our long-term commitment to revitalization. In particular, the plan ignores the critical role that international talent has to play, and I’m convinced that blind spot will bite us in the long run.

Prioritizing stability over ideology

Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.

– Charlie Munger

This is probably my favorite part of the entire action plan, for one specific line: “reform power markets to align financial incentives with the goal of grid stability.”

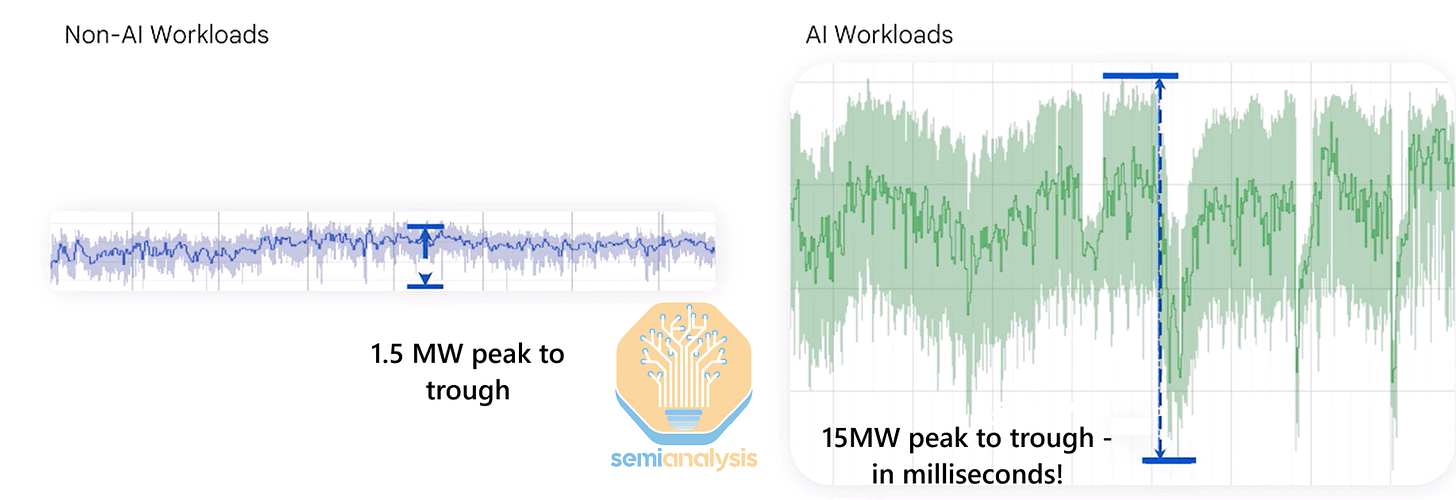

It starts by reiterating that our electric grid is critical for all aspects of the modern economy and must be safeguarded, while acknowledging that in its current form, it’s unsuited for the increased pressures of AI datacenters. Training and deploying large-scale models carries high load variability (±15MW peak-to-trough in milliseconds) and therefore very real blackout risk for energy grids which cannot absorb that much demand-time.

The safest way to accomplish this is by introducing large volumes of “baseload” power - reliable, stable sources like natural gas, hydropower, and nuclear - to create a high watermark in excess of that demand variance, say 85% of peak.

Excess power from these projects during downtimes can be added back to the grid, enhancing stability.

During peak times, pairing these projects with battery energy storage systems (BESS) can significantly help with sub-second ramps, since lithium ion batteries excel at this.

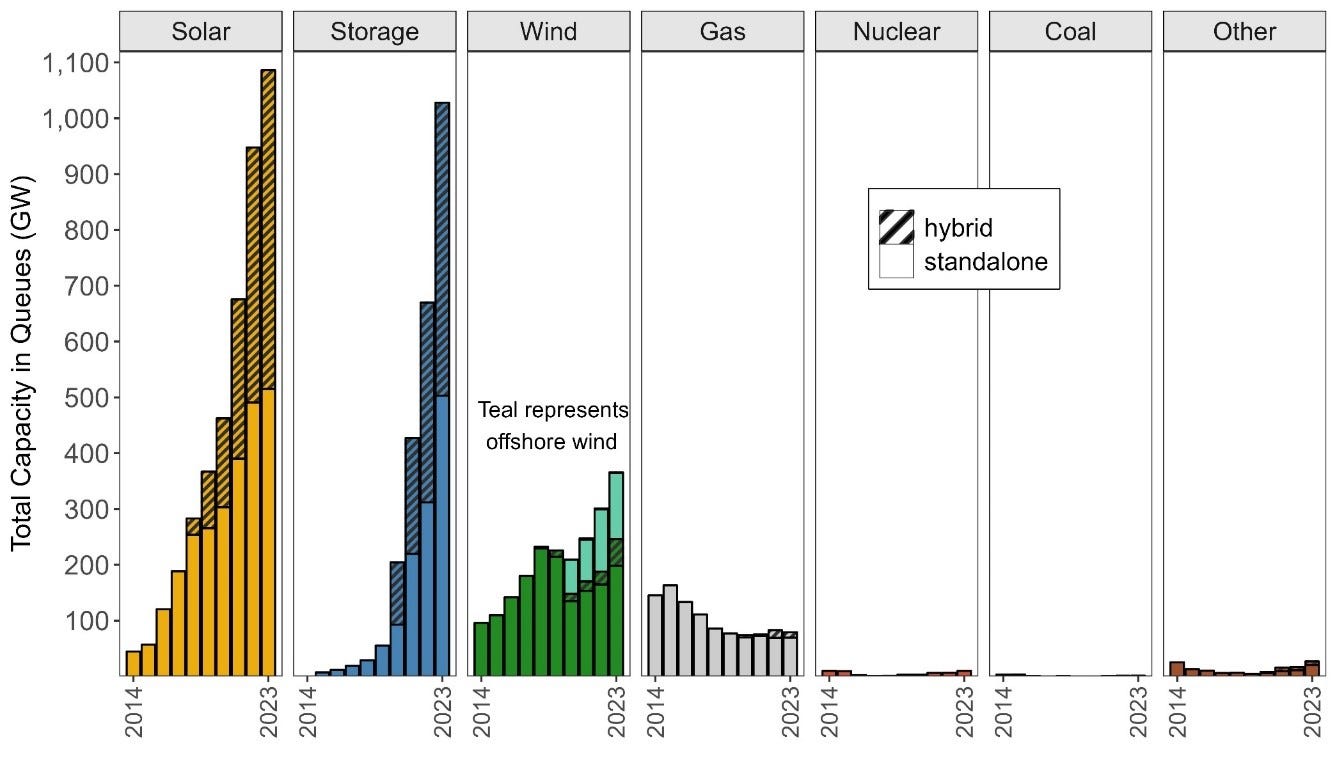

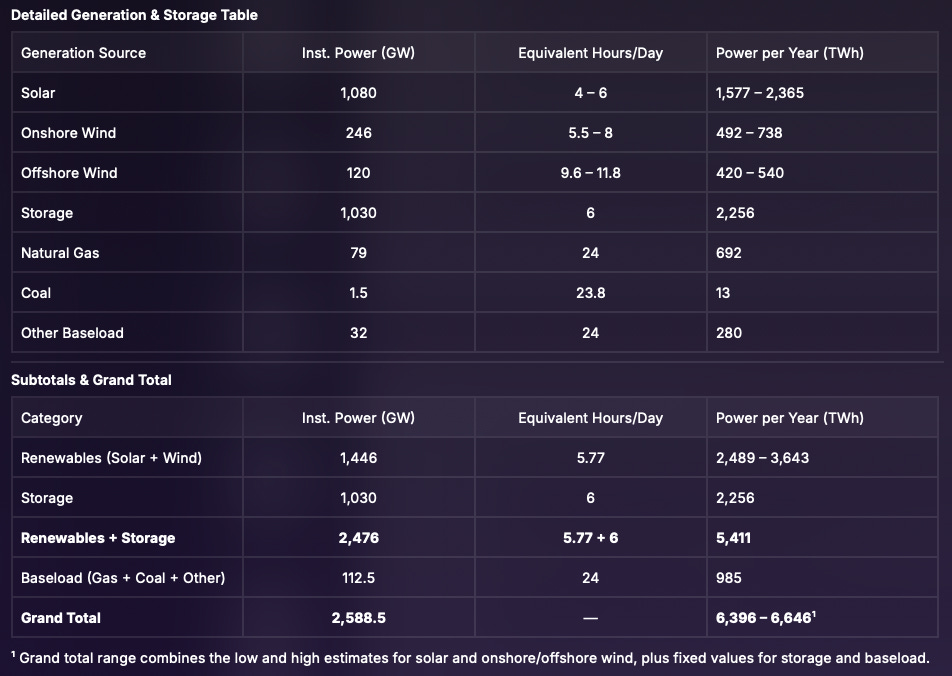

Up to now, the interconnection queue has not at all resembled these needs. In the most recent report from the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, of the 1,570 GW of new generation proposals still in the queue (which takes 3 to 8 years to clear right now, by the way), a meager 118 GW (7.5%) of new power fits this baseload profile. Intermittent generation like solar and wind dominate the queue, commanding 1,086 GW (69.1%) and 366 GW (23.3%) respectively.

A good deal of this buildout was no doubt influenced by the prior administration’s last-minute bum rush to push out $400BN of debt financing to renewable energy projects… influenced by ideology, not by the practical needs of energy-compute infrastructure in the new economy.

Not all power is equal

Remember, we measure power not just in instantaneous terms (gigawatts) but in time-denominated terms (gigawatt-hours). So when comparing power from different generation resources, you need to consider over what period of time that’s deployed.

Since battery duration is limited to just a few hours (1 to 4 commonly), we can’t rely on BESS alone to handle these loads. When paired with renewables, developers have to significantly overspec in order to provide continuous power.

Using Las Vegas as a sunny example, irradiance patterns allow for delivering 1 kW of continuous power via 5 kW of solar panels paired with a 17 kWh battery

Scaled up to a 100 MW AI data center, this would require 500 MW of solar panels (making it the 6th largest deployment in the US) and 355 MWh of storage supported by at least 91 Tesla Megapacks (4-hour configuration)

Recall from earlier that our current delta with China’s generation capacity is roughly 6,000 terawatt-hours (TWh) - that’s 6 million gigawatt-hours (GWh). If we waved a magic wand and activated all of our interconnection queue simultaneously, could we close the gap?

By some reasonable estimates, yeah, we could narrow or even close it entirely. But those hours aren’t uniformly distributed throughout the day. There’s no reason why baseload power can’t be augmented with renewables and BESS, but putting all your chips in the intermittent basket with the fluctuations AI workloads introduce doesn’t make sense. Hence the Plan’s emphasis on comprehensiveness, stability, and consistency.

Cutting the red tape

Most data center infrastructure projects require significant upgrades to grid infrastructure to handle contemporary AI workloads. The Action Plan more or less gives the green light for data center-related projects to either fast-track or bypass reviews and permitting, so long as the site is consistent with the size of a modern AI data center. What that size is specifically remains unclear in this document.

Aside from energy and labor, seeking relevant permits and environmental reviews do take a significant portion of time in new and brownfield builds. This administration calls for using exclusions granted by existing regulations to speed things up, rather than go through Congress:

Establishing new Categorical Exclusions under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) to cover data center-related actions

Expand the use of the FAST-41 process (Title 41 of the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act) for speedier reviews and processing

Make Federal lands available for data center construction and the construction of power generation infrastructure for those data centers

This is generally good news, especially on the third point, which I detailed in a May submission to the Department of Energy’s RFI for building AI data centers on federal lands. A coalition of industry reps from energy, AI, and power that I gathered identified and proposed the most suitable DOE-owned sites that could house energy-compute projects, based on a number of factors. It’s good to see the DOE following through on this.

Restore American semiconductor manufacturing

Perhaps in a future post I’ll give a history and near-term forecast of the US semiconductor industry. For now, all you need to know is that while American companies like NVIDIA, AMD (as well as new entrants like Positron and Groq) may lead fabless chip design, on-shore production of bleeding-edge nodes is in a pretty dire state:

Intel’s recently decided to shelve its 18A (1.8 nm) process in favor of diverting resources to 14A (1.4 nm) underscores the challenge

Analysts warn Intel has roughly 18 months to land a “hero customer” for 14A… otherwise its cutting-edge fabs could be abandoned altogether (forfeitting any further CHIPS Act disbursements)

Even foreign foundries with US fabs are facing problems. Samsung’s $44BN Texas mega-fab - originally slated for 4nm mass production - has struggled with yields and customer commitments, prompting executive leadership to declare a 6 month transition window to 2nm, and delay 1.4nm to 2029 while they dial in reliability

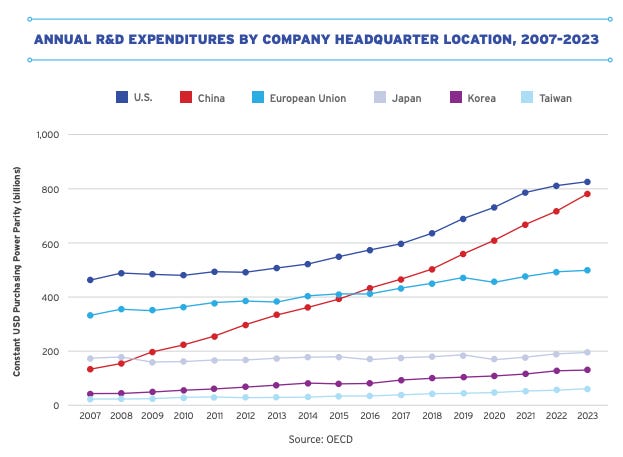

The US government does wield some levers. In the next decade, the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) projects the US fab capacity will grow by 200%+ over the next decade - doubling the global average - and American semiconductor R&D outlays exceed $60BN, the highest in the world today in purchasing power parity (PPP), despite our tax incentives lagging peer nations.

But funding is just one part of the problem, as our prior examples show. If domestic champions like Intel can’t make the cut meritocratically, then we shouldn’t be casting taxpayer pearls before swine.

To that end, the SIA projects a domestic shortfall of 67,000 workers across the semiconductor manufacturing chain - device and machinery manufacturing, design, and EDA tools - by 2030.

Given that this section imposes a sensible constraint of “lead[ing this] revitalization without making bad deals for the American taxpayer” (emphasis mine), I fear that without significant advances in domestic semiconductor talent to cross critical yield thresholds (70%+) in a short period of time, domestic manufacturing will continue to be a satellite for foreign fabs like TSMC and Samsung, while domestic players only satisfy trailing edge process nodes.

This isn’t the worst possible outcome, but it does put the U.S. at a disadvantage if China continues to improve in fabless chip design and domestic manufacturing.

We need international talent. Full stop.

Even if the U.S. fast-tracks every permit, reopens every chip fab, and supercharges the grid, we still face a crash course in human capital. We’re not just talking about the semiconductor shortfall - we need tens of thousands of electricians, HVAC technicians, network engineers, and other tradespeople to support this buildout.

Yes, the administration’s push for national, state, and local workforce programs is welcome - industry-driven training, revamped apprenticeships, early-career exposure and the like. But this transformation will take at least a generation without top-tier international engineers and technicians.

Nativist tit-for-tats on Chinese student visas are worsening, not improving, the problem. I’m not even coming from an emotional place on this, despite my obvious affinity for both countries. I’m stating a fact that in many STEM industries, even in our most advanced AI research labs, the diffusion of Chinese talent is impossible to ignore. Half of Meta’s Superintelligence team got their undergraduate degrees in China, for Christ’s sake.

This is not to say that domestic employment concerns are unwarranted. There are some common-sense changes we can implement that achieve a favorable middle ground, like revamping the green card system to a merit-based skills prioritization matrix rather than a country quota exercise. Permanent residency for critical roles like semiconductor engineers, AI researchers, etc. should be sought.

But what is the benefit of antagonizing those talented young engineers, if only to send back home and accelerate China’s progress further? As Kaiser Kuo said in his response “An Own-Goal of Historic Proportions,” Chinese officials were likely publicly condemning the move, but privately popping the baijiu.

Meanwhile, at that same industrial park in Hangzhou I mentioned earlier, I asked a senior government official what their policy was towards foreign talent. What kinds of personnel were they looking for, and what support (if any) did they offer? I’m paraphrasing his translation, but

“Foreign talent in key industries, especially PhD holders, are more than welcome. In addition to the office lease discounts and apartment leasing subsidies for college graduates, overseas talent can get free housing ($1M to $2M USD)”

I’ve heard of such programs in China’s broader “Thousand Talents Plan,” but it was my first time seeing it face to face, despite the escalating tensions.

Even if we solve our energy problems… even if we cut all the red tape… we risk building golden factories with empty benches. Unless the administration pivots here, our nativism will kneecap our ambition.

III. Lead in International AI Diplomacy and Security

Overall, this part of the action plan falls woefully short. Predictably, the administration pushes for a unilateral promotion of American AI systems, compute hardware, and standards throughout the world. It’s also logically inconsistent, or at least overestimates the negotiating leverage Americans have in bilateral trade of these systems outside of a vacuum.

Consider the U.S.’ failed efforts to limit Huawei’s 5G diffusion throughout the developing world. I’ll briefly summarize those points below, then apply them to the Action Plan’s stated intentions against the status quo:

Recap: Why the Huawei 5G Ban Failed

U.S. “Security Threat” Narrative. Washington repeatedly labeled Huawei “an arm of the Chinese state,” warning that its 5G equipment could be used for espionage or cyber-sabotage. Brazilian and South African officials pushed back, demanding concrete proof of back-doors or spying, but no transparent or legally vetted evidence could be shared.

No American 5G Champion. Meanwhile, as a counter, no U.S. or U.S.-allied vendor offered a full end-to-end 5G solution at Huawei’s price and scale. With neither domestic champions nor subsidized U.S. exporters stepping up, local operators saw little downside in choosing Huawei for cost-effective, rapid-deployed, field-proven equipment.

China’s “Digital Silk Road”. Beijing wove Huawei into broader “Digital Silk Road” and BRICS-era cooperation, offering low-interest loans, technical assistance packages bundled with infrastructure financing, and joint development labs and exchanges. As usual, this was a financial “no strings attached” proposal boosted by multilateral collaboration on shared principles for digital development.

Taken together, these factor left Brazil, South Africa, and many countries free to integrate Huawei into their 5G roadmaps.

The more things change...

However, the current situation is not completely congruent. The first item in this section advocates for exporting America’s “full technology stack – hardware, models, software, applications, and standards.” That’s a genuine step up from 5G, since American labs and chip designers currently own the leading edge.

But the stack is more than just chips and models. As mentioned earlier, AI datacenters have insanely high load variability and require significant energy infrastructure upgrades. Without behind-the-meter generation, high-voltage transmission lines, battery energy storage systems (BESS) and the like, many developing countries wouldn’t be able to locally deploy complete stacks even if they wanted to.

China bundling energy infrastructure investment and financing together with datacenter rollouts would be a successful repeat of its 5G playbook. And early innings of that strategy were on display in the WAIC expo hall.

...The more they stay the same

Because energy and digital infrastructure rollouts are tightly interdependent, local operators and regulators may naturally gravitate toward China’s packaged offerings, especially where BRI momentum is already strong.

Further, ceding the field on AI safety and governance presents too wide a gap that China’s “AI Governance Action Plan” is primed to fill. Beijing called for convening governments, industry and civil-society around multilateral standards, capacity-building programs and joint R&D - while at WAIC not only did no Trump administration AI safety officials show, the only representative from a US AI lab even proposed an outright ban on open-source models, arguing “you wouldn’t give everyone a nuclear bomb.” From Paul Triolo:

The lone official from a leading US AI lab, Dan Hendrycks, raised eyebrows by essentially calling for a ban on open source/weight models, while some Chinese AI safety experts called for just the opposite, urging the US to force proprietary model developers such as OpenAI and Anthropic to open source their models, arguing that this was a better way to ensure the safety of advanced models going forward.

To say Hendrycks read the room badly would be an understatement. While he is a respected safety researcher and red-teamer, his position leaves no room for negotiation or joint development, is in contrast to the Action Plan’s commitment to open-source, and left most of the room feeling puzzled.

Overall, I’m getting a strong sense of déjà vu: Beijing’s “inclusive multilateralism” mirrors the Digital Silk Road playbook, whereas the US push to “Counter Chinese Influence in International Governance Bodies” suggests that any multilateral consensus that includes Chinese participation is inherently suspect, prejudicially undermining sovereign decision-making.

I’ll stop my comparisons here, as Paul goes into excellent depth in his latest post on his Substack, AIStackDecrypted, which I strongly agree with and encourage you to read.

Conclusions

The American AI Action Plan is a welcome signal that Washington is waking up to what’s necessary to succeed in the new economy:

Open-source wins. It embraces open-source and open-weight models - crucial to developer and industry soft power

Grid stability over ideology. It confronts the brutal physics of the grid, without an ideological slant - no electrons, no intelligence economy

Yet it tiptoes around two levers that decide whether the American hare will actually start closing the gap:

Talent. 67K semiconductor hires plus tens of thousands of skilled trades won’t materialize out of thin air. Skills-first green cards, visa-to-apprenticeship tracks, and a reversal in the student-visa nonsense is critical

Diplomacy. Export controls and America-first platitudes aren’t effective strategies. Allies need a full AI stack bundled with infrastructure, financing, and standards toolkits, but they need it on a multilateral basis, not one-way

So yes, it’s a start. But we need more than an Action Plan… we need a Marshall Plan. Alliances built out of watts, wafers, workers, and a shared vision of the future.

Because there isn’t a finish line. There’s just progress.